- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

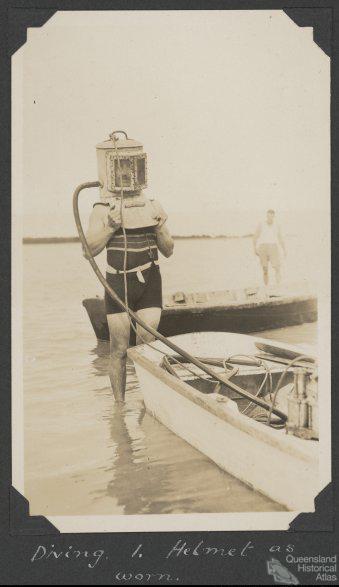

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

Copyright © Queensland Historical Atlas, 2026. All rights reserved.

ISSN 1838-708X