- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

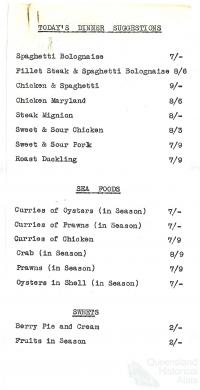

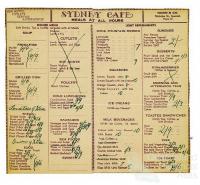

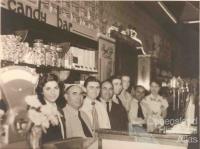

Toni Risson Toowoomba, Cunnamulla, Maryborough, Muttaburra ... from busy coastal cities to one-street settlements in the far west and tropical north, every town in Queensland had a Greek café. Whether they were elegant three-story affairs that catered for weddings or narrow shopfronts that concentrated on takeaway, Greek cafés were open from 6am to 11pm seven days a week except Christmas Day and Good Friday. The food was good. There was plenty of it. And it was cheap. They were the McDonalds of their time. During the heyday of the Greek café in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, regional cities sustained up to a dozen cafés, which were packed out on Saturday nights. Ipswich in southeast Queensland, had a dozen Greek cafés in the CBD in the 1940s. But Greek cafés were more than food outlets; bustling to the clatter of silver cutlery, the hiss of sizzling steaks, and the swoosh of soda fountains, popular cafés like Londy’s in Ipswich and Cominos’ in Cairns were the hub of their communities. The Greek café is an Australian icon and a uniquely Australian phenomenon.

The Greek shop-keeping phenomenon

Historian Hugh Gilchrist claimed, ‘If there is a single word which summarises the lives of most Greeks in Australia early in the 20th century it is shop-keeping’. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries thousands of Greeks fled poverty and political unrest in their homelands in search of a better life. Most were single men. In Australia they worked as market gardeners, canecutters and the like, but by the 1890s a surprising number had gravitated to food service industries. Many did not return to their homeland as planned but married Greek girls by proxenia, and as the twentieth century progressed women and children played significant roles in Greek shops. How the Greek shopkeeping family became a quintessentially Australian phenomenon is the story of the Greek café.

Arthur Comino from Kythera opened the first Greek fish shop in Oxford Street Sydney in 1878. Exploiting the craze for oysters, Comino prospered and began sponsoring fellow countrymen’s passages to Australia. The resulting chain migration meant that 70% of the 400 Kytherian immigrants living in New South Wales by 1911 owned or worked in Sydney oyster saloons. Greek shops soon dotted the Australian landscape as migrants from all over Greece, having been ‘apprenticed’ in Sydney, moved out into rural New South Wales and up into Queensland. They opened shops like the Athens Oyster Saloon in Longreach and these were the precursors of the Greek café.

The Greek café

From the second decade of the twentieth century, female waitresses replaced male staff, kitchens served a greater range of food, and the title ‘Café’ replaced ‘Oyster Saloon’. In addition, cafés adopted the ‘classic form’, which has come to define the iconic Greek café. Often called the Paragon, the Majestic or the Australia, the café with its ritzy Art Deco façade was easily located in the main street, where shoppers, country folk, and travellers pushed through plastic strips that were strung across the doorway to deter flies. They passed the confectionery counter, behind which gold lettering on a mirrored sign advertised homemade Icy-Cold Lemon and Orange Drinks. They nodded to the proprietor, waiting to dispense milkshakes in frosty, anodised containers or foaming ice-cream sodas from chrome soda fountains on the milk bar, before jamming into wooden cubicles along the side walls. According to historian Denis Conomos, an electrically-refrigerated milk bar that chilled water, milk, and ice-cream and was equipped with a malted-milk mixer, soda fountain, fruit-juice extractor, and ice-cream maker, was a feature of the new-style Greek café that appeared throughout Australia during the 1910s.

Fish ‘n’ chips at the dago’s

Because they flourished at the interface between an anglophile Australia and a new wave of ‘foreigners’, Greek cafés offer a means of understanding the relationship between Greek and Anglo-Celtic Australians. Proprietors were well-respected in their communities and local women who worked for them report that the Greeks treated them like family. But most Australians referred to Greek immigrants as ‘dagos’ and non-Greek cafés in Queensland towns bore signs urging customers to Shop here before the Day Goes. The latent hostility towards proprietors surfaced on Saturday nights when drunks rolled into Greek cafés for a meal.

Significantly, Greek cafés did not serve Greek food. They catered instead for the British-Australian predilection for steak, chops, poultry, pork fillet – accompanied by fried eggs, chips, salad or boiled vegetables, sliced white bread and butter – meat pies, mixed grills, toasted sandwiches and coffee. (The mixed grill, which consists of a steak, a chop, two sausages, two fried eggs and two rashers of bacon accompanied by a large grilled tomato and two slices of white toast with Worcestershire Sauce readily available, is the epitome of this diet). Many also maintained the connection with seafood, selling oysters, prawns, fresh and cooked fish and creating in the Australian imagination an enduring association between Greeks and the warm, salty smell of fish ‘n’ chips wrapped in newspaper. Harry Tanos of Ipswich’s Sydney Café commonly peeled five x 150 pound sacks of potatoes and cleaned and cooked 600 pieces of fish on Fridays during the 1950s. Given that Peter Londy did a similar trade at the nearby Londy’s Café, Ipswich residents consumed over a thousand pieces of fish on Fridays during this period.

Proprietors knew what Australians wanted and gave them plenty of it whenever they wanted it. They adhered for decades to this simple business principle and a policy of cheap prices and warm hospitality. While proprietors claim they would have been lynched if they had served Greek food like spinach pie or dolmades in their cafés, as employers, friends and neighbours they did eventually change the face of Australian cuisine. First sampled in café kitchens or across suburban backyard fences, the Mediterranean diet of basil, garlic, yoghurt, olives, olive oil and chunks of unbuttered bread is now part of the Australian lifestyle.

Greek cafés and milk bars reflected the social tradition of the Greek kafeneion or coffeehouse and were a vital part of the social fabric of Australian culture for much of the twentieth century. They enabled generations of Greek immigrants to become part of their adopted homeland and also popularised American food-catering ideas like the soda fountain and milk bar. But pre-packaged goods, supermarkets, fast-food chains, television, super cars and highway bypasses, even the declining influence of Catholicism and its hold over Australian eating patterns, contributed to their gradual demise in the closing decades of the century. Despite its iconic and singular status, the Greek café has all but disappeared from the Queensland landscape.

Copyright © Toni Risson, 2010

Related:

Queenslanders After the pictures on Saturday nights the town made for Comino’s to eat mud-crabs that turned brick red when boiled or grilled trumpeter or steaks heaped with onions while Georgi, his coat off and gold watch-chain hung with medallions across his waistcoat, his thin hair plastered in strands across his polished skull, moved among the tables, laughing and shouting orders, while Momma, only five feet one inch high and almost as wide, and strapped in corsets that lifted her large breasts under her chin and almost choked her, sat behind the till and smiled at the room as she breathed deeply and smoked a black cigar, an eccentricity the town endured because everyone liked Momma and because she was only a Greek.

From Ronald McKie, The mango tree, Sydney, Collins, 1974